Molds for plastic injection of the regular LEGO bricks are made of two pieces, one with a negative shape of the top of the part to be molded (this is the female part of the mold and is called the cavity) and the other carries a male-piece and is called the core. Once closed, the space between core and cavity has the exact shape of a brick and is pressure-filled with molten plastic and a part is obtained. For small parts a mold may allow the simultaneous casting of several units - similar or different. The plastic may be injected from one or from several points in the periphery of the mold and is channeled to each cavity. The molds are then allowed to cool and some seconds later the parts are cold enough to be solid and the mold opens to allow their removal. As the mold closes again, the cycle is complete.

When the mold opens it is desirable that all parts molded stay connected to one of the sides of the mold, often the core where they will be totally exposed and ready to be ejected, e.g. by the movement of a mechanical system, or by a gust of compressed air. The parts are connected by a matrix made up of a plastic shape of the injection channels (called the sprue system) and the whole set is ejected together. At the time of ejection each part is automatically cut free of this treelike matrix but a small burr will result, marking the position of the pip or pips trough which the molten plastic entered the mold unit.

The illustration below, reproduced from:

http://www.brothers-brick.com/2006/06/20/lego-factory-mold/ ... shows a mold for 2X3 elements. It will be noticed that in this case the mold has 8 similar cavities and thus each cycle produces 8 similar parts.

An important point is that molds are cut from steel and are hardened after machining which usually renders unprofitable any later alteration. For that reason, even when small carving alterations (like the addition of a logo) are needed, new molds have to be made. However, when the alteration is possible by cutting-off a protrusion of the mold, the mold may be thus altered, although a burr will probably result.

|

|

|

|

Although several parts are produced in each cycle of operation, they are not exactly identical. Each cavity from an early mold was originally machined and hand-finished separately and has small burrs that will be reproduced in the parts, somewhat as a gun barrow imprints bullets. However, manufacturers need a faster way to identify mold cavities producing defective parts (e.g. because of the accumulation of residues- see image left) so that they may be intervened promptly. And so, when a mold is used to cast replicates, each cavity is often individually identified with a number.

The earliest LEGO parts were not identified as to the mold unit that cast them, probably because there were only one or two molds making only a few bricks in each cycle and when there was a problem, the mold unit affected was immediately identifiable. But by the mid 1950s, when more than one mold unit produced the same part, each mold unit began being identified by a code.

With few exceptions, most all early LEGO molds made after 1953 have their units identified by a number or by a code made from a number and dots, either imprinted in the mold by hand engraving, or else machine-engraved. After circa 1962 a system using a number and an alphabet character started being used.

Since molds did wear in a few years time (typically one to four years, depending on the mold alloy and on the rate of production) the numbers in a brick, associated to other characteristics, may help date a single brick. But, note, there are a few irregularities: unnumbered bricks (mold unit nr 0 was not inscribed), replicated numbers, and even numbers inscribed over others. These may result from production by multiple factories or injection machines, chronological succession of similar molds at the same location, mistakes at the time of production of the mold, later corrections and other causes. But problematic discrepancies are seldom met with in the early bricks of Danish origin that will be the subject of our study.

The 1X2 bricks on the left side illustrate the numbering system used in most cases from circa 1954/55 up to, at least the early 1960s. The "6" on the middle brick has a dot at the base to tell it apart from a "9".

On the right side, a numbering system briefly used in the 1X2 bricks in the mid fifties. Here the individual molding units are identified by a system using both numbers and dots differently positioned around the numerals.

Another important mold-related theme is the ejection system. When the mold opens, all the parts and the sprue should remain positively attached to one of the sides, so that the whole may be subjected to the ejection and cutting actions, freeing the mold for the next cycle.

Several early LEGO bricks have internal ribs, as seen in the picture of the red brick below left. Those ribs vary from mold to mold (they may be longitudinal, transversal, integral or fractional) and they are thus an important identifying characteristic. My best guess is that they are designed so that when the mold opens all the bricks and the sprue will keep solidly connected to the core side of the mold, to be ejected from there by an automatic system (an ejector plate which frees the parts from the mold and, at the same time, cuts the sprue, leaving only the pip mark).

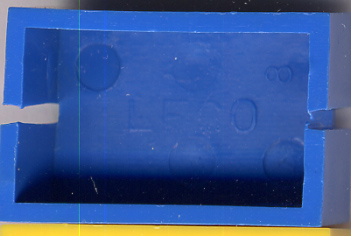

Some molds have ejector pins in them. These are long rods symmetrically arranged that thrust forward after the mold has opened and the part is cold enough, and eject the bricks. Again, the face of the pins contact the brick during the plastic injection process, leaving circular imprints (see figure of the blue brick below right) that are important clues to identify families of molds.

|

|

|

A

longitudinal rib is clearly seen near the inside edge of this 2X4vs02a

|

The

imprints of four ejector pins on the underside of a 2X3vs01c

|