|

ART

DECO HOTEL LUGGAGE LABELS

by

JOAO-MANUEL MIMOSO

|

| 1- ORIGINS |

|

|

. |

|

|

| Not

all Art Nouveau design and graphics were based on the languid curves lines

that some considered decadent. Some trends within the Art Nouveau movement

favored elongated and predominantly rectilinear forms as seen in the decoration

of the label at left. |

|

| . |

|

| |

By

1905 Austrian artists of the Wiener Werkstätte were using wholly geometrical

and often linear graphic solutions of great originality and strength. They

are classified within the Art Nouveau movement but most of their industrial

design, architectural- and art work of, say, 1908 would not seem out of

place twenty years in the future. It is to the everlasting credit of the

Austrian genius that Wiener Werkstätte labels, like the one at right,

are only datable within a 20-year uncertainty period. |

|

|

. |

|

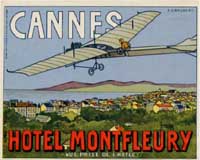

Art Nouveau practitioners recognized that, although the flowing lines of

their style adapted well to the forms of Nature, the linear and geometric

shapes of industrial products such as trains and cars could not be properly

rendered and were thus best avoided as a main subject or decoration theme.

However, others were finding inspiration in those complex machines made

of simple geometrical forms. |

|

| . |

|

| |

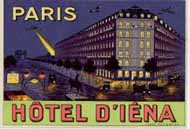

The

so-called machine-aesthetic is not an art movement but rather a denomination

including design of all kinds that accepts the sound geometrical principles

of machine-made products and adapts all its elements to the primacy of such

shapes. The image used in the label at top left dates from circa 1909, while

the label at right probably dates from around 1914. Both exemplify the clean

machine-aesthetic in the rendering of architectural elements and the lettering. |

| |

|

. |

| 2- THE AVANT-GARDE

MOVEMENTS |

|

|

. |

|

|

| The

vitality of Art at any given period might well be measured by the number

of avant-garde movements: people with new, often cranky-sounding ideas that

eventually find acceptance. One such movement was Italian Futurism, started

by F. Marinetti in 1909 as a revolution that advocated typography as art

and proposed disharmony through the use of up to twenty fonts in three or

more colors in any one page. From 1919 the Bauhaus produced examples that

were inspired on those and other principles. Bauhaus graphics made use of

several different font types and simple geometric forms, often in black

and red, as in the label at left. |

|

| . |

|

| |

Another

avant-garde movement that also influenced Bauhaus graphics was Russian Constructivism.

First stated shortly before the October Revolution, the movement's nonfigurative

visual vocabulary relied on brightly colored (often angular ) shapes, bold

lettering and collage designs. Communist in inspiration, the constructivists

were nonetheless soon eyed with suspicion by the Soviets. Its short life

in a country in turmoil makes true constructivist designs some of the rarest

and most desirable of all hotel labels. |

|

|

. |

| The

origins of Cubism are still earlier than those of Futurism, being

traceable to experiments in color and shape started by Picasso and Braque

in 1906. Pure Cubism aimed at conveying the essence of objects through a

perspective of geometric shapes and was averse to an excess of color. Cubist

hotel labels, like the one at left, are very unusual. |

|

| . |

|

|

| 3- THE HEYDAY

OF ART DECO |

| |

|

. |

|

| |

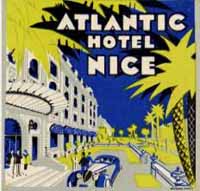

Plain

Art Deco was a global style that flourished between wars and was characterized,

in its graphic avatar, by an overall preference for simple and often striking

geometrical shapes, elongated figures and objects, bright contrasting colors

and special, usually non-seriffed typefaces (serifs are the small marks

on the tops and bottoms of types as found on classical fonts like Times

New Roman that browsers use as default, but not on Helvetica in

which this text is written). |

|

. |

| The

name Art Deco was coined in the 1960s after the 1925 Paris International

Exhibition (Exposition Internationale Des Arts Decoratifs

et Industriels Modernes). In its heyday it was known simply as the Style

Moderne. Thanks to its bold rectilinear forms, Art Deco easily integrated

cars, planes and other technological symbols of the modern world. The futuristic

shapes and colors also conveyed the optimism of the 1920s, when its popularity

peaked. |

|

| . |

|

| |

The

homeland of Art Deco is often said to be France. This statement is based

on the fact that the style triumphed at the 1925 Paris Exhibition and through

it received a wider recognition than ever before. However its roots stemmed

from many countries: not only France, but Austria, Germany, Scotland, Belgium,

Russia, (...), and particularly Italy can claim fair shares of credit. |

|

|

. |

| An

important source of the individuality of the superb Italian Deco was Futurism,

briefly mentioned above. In his manifestos Marinetti advocated an uncanny

mix of Italian nationalism, militarism, and 'the new religion of speed',

as expressed through cars and airplanes. From typography Futurism spread

to other fields of graphism and after some "taming" that did away

with its most extreme propositions and hybridizing with other deco trends

it came to be the graphic style of Mussolini's Italy. |

|

| . |

|

| |

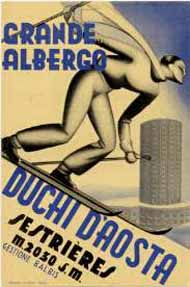

Futurism-inspired Italian Deco

uses characteristic hand-drawn lettering, often with several fonts of

different colors to the page.

Another distinguishing characteristic of typical Italian designs is the

widespread use of the airbrush grading of colors into white, as illustrated

by some of the most representative labels of the period. The very best

designs, often wasted in such trivial items as chocolate wrappings, covers

for minor magazines, or calendars, are as strikingly fresh and attractive

today as they must have been in their time. The

label at right is characteristic of Italian Deco. There are at least four

different fonts in three colors; some of the text is at an angle with

the rest. The color of the elongated skier was airbrushed.

|

|

. |

| During

the 1920s, Art Deco found new grounds and flourished with unsuspected vigor

in the United States. After all, was this not an art for the Age of the

Machine, which America symbolized above all others? As far as hotel labels

are concerned, there are tens of American deco designs but few to really

sparkle a choosy collector's interest. Noteworthy exceptions are a series

of octagonal labels, of which one is displayed at left, in which the frames

show unusual designs inspired by deco architectural decorations of the time. |

|

| . |

|

| |

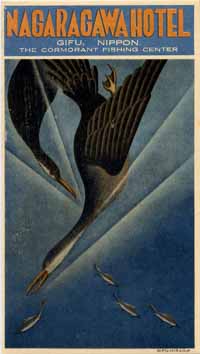

In the end, Deco spread the

world.

In Japan, it drew with unexpected

success from the same forces that fought for the modernization and industrialization

of the country. There is a surprising number of Deco Japanese labels,

of which the example at right is maybe the most extraordinary.

In colonial territories, the

style spread from the modernities of the home country, often through designs

ordered from Europe or by the efforts of one single local designer whose

style was later taken by others. Hotels

in French and Italian N.Africa used a wide variety of Deco labels ordered

from France and Italy; the Dutch East Indies, on the other side, were

also a Deco oasis but mostly through the efforts of local designers of

which the most prolific was Jan Lavies.

|

| |

. |

| 4-

THE LAST DECO LABELS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

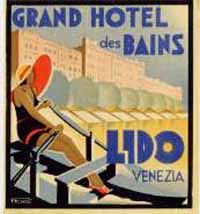

Then as today, modernity clashes

with conservative views and Art Deco never really caught with some people.

Many hotel managers specifically ordered labels made "in the old

style". This was particularly the case for the high-class Palace

Hotels and for other exclusive town hotels- their owners were less willing

to risk on novelties than owners of less pretentious establishments. It

was thus that printers like Richter could survive even though (with very

few exceptions) they did not design Deco labels, while others, like Barabino

& Graeve who probably printed the label for the Grand Hotel des Bains

in the Lido of Venice, practically used exclusively the new style. It

is also for the same reason that Deco labels are more common in vacation

spots than in large towns.

|

|

| |

|

| |

According

to most sources, Art Deco died at the onset of the Second World War. Yet

its attractive styling and modern looks were not really buried and many

hotel labels of the 1940s and 50s can be said to be closer to Deco than

to any other style. This is particularly true of labels designed for hotels

within the Iron Curtain, although the style was, by then, tired and the

designs were not as attractive as they had once been. Yet, and as far as

labels are concerned, in a way Deco lived until the demise of the luggage

label itself. |

| |

|

|

| |

Go

to the index of hotel label pages |

Joao-Manuel

Mimoso |

| |

|

|

|

| .Lisbon,

Portugal |

|

|

|

|

first uploaded

2000-09-05

reviewed 2002-12-20

|

|

|

|